Remarks by Julie D. Soo

for the World Premiere of “Angel Island”

Friday, October 22, 2021, 8pm, Presidio Theatre, San Francisco, CA

I am honored to be invited by Del Sol to provide remarks giving context to the premiere of Huang Ruo’s Angel Island Oratorio as part of Del Sol’s “The Angel Island Project.”

For me, like many in this audience, the story of early Chinese immigration and Angel Island is personal. I am a fourth-generation San Franciscan on my mother’s side of the family and second-generation on my father’s side. On both sides, I have ancestral roots from 順德 Seun Dak (Shunde), now a district of 佛山 Fut Saan (Foshsan) City, of Guangdong Province, along the Pearl River Delta. Our maternal grandfather – Gung gung – was born in 1892 in San Francisco. His parents – our Tai Gung and Tai Po – were of means, mercantiles, who arrived at 金山 Gam Saan – Gold Mountain – America, the land of opportunity, in the late 1880s.

Tai Gung and Tai Po returned to China, years later relocating to Hong Kong, and left Gung gung to his schooling in San Francisco. As a young adult, Gung gung went to China to join his parents and complete his higher education. He married Po po, our maternal grandmother, who lived a life of privilege in Seun Dak. Gung gung returned to San Francisco to set up a home before sending for Po po around 1915. In spite of being married to a recognized U.S. citizen, Po po spent an estimated three to six months on Angel Island before being allowed to join Gung gung. To note, Gung gung and other Chinese like him born on U.S. soil were not recognized as citizens prior to the retroactive application of U.S. v. Wong Kim Ark wherein the U.S. Supreme Court in its March 28, 1898 decision articulated the term “birthright citizenship.”

Some episodes in life are too painful to speak of. Po po never spoke of her days on Angel Island. Her grandchildren remember her best friend, Yi Po, or second grandmother. Through opaque references, we learned that the two had become friends while in detention on Angel Island. Gung gung never told any of his six children about his uncle being killed in 1901 by a white mob tearing though Chinatown looking to kill Chinamen. The police never came and there was no justice. He was only able to tell my father, his son-in-law. Gung gung was just nine-years-old when his uncle was brutally taken and as an octogenarian, maybe he needed to share the burden of that story.

Angel Island – Not an Ellis Island of the West for Chinese But a Deportation Center for Chinese

Angel Island was not an Ellis Island of the West for Chinese but a deportation center for Chinese. The stories of the harsh conditions faced by Chinese immigrants between 1910 and 1940 are partially documented by poems carved in the walls of the Angel Island Immigration Station barracks. In the backdrop, the virulent anti-Chinese sentiment had been clear after the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad in 1869 when San Francisco and California legislators no longer had a need for Chinese competing in the labor pool.

All politics is local. The anti-Chinese sentiment that began at the San Francisco Board of Supervisors spread to the California Legislature and then to Congress. The Page Act of 1875 barred Asian women, particularly Chinese women, from migrating to the United States, providing Chinese men incentive to leave the United States. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 that followed barred Chinese laborers from entering the United States and is the only law ever barring a specific ethnic group from immigrating to this country. That Exclusion Act would last for 61 years, keeping families forever separated. Even after its repeal in 1943, entry of Chinese was limited to 105 per year until increases under the Immigration and Nationality Acts of 1953 and 1965.

While Ellis Island stood for welcoming its European immigrants, on Angel Island the populations were separated by race and Chinese endured the harshest conditions. Non-Chinese were processed in a matter of a few weeks at most. Chinese often waited months and even years, subjected to humiliating group medical examinations and highly technical interrogations. Some were deported back to China after waiting more than two years. Many ended their own lives, isolated from any communication and unable to endure the unknown.

Music a Universal Language

The poems carved in the walls of Angel Island were by immigrants from Southern China, mostly from the Toisan area as had been the case with gold miners and railroad workers generations before. The poetry if not read in Cantonese Guangdong wah or the sub-dialect Toisanese Toisan wah or Hoisan wah loses the cadence and rhyming. Music – like mathematics and science – with symbolic language transcends the geography of spoken and written languages, dialects and sub-dialects. Music universally captures the emotion and heart of human existence. I have heard just an excerpt of Master Huang’s Angel Island Oratorio: the enveloping richness of the instruments and voices stirs the untold stories of hopes dashed, lives lost, as well as the will of survival to forge a new life on Gold Mountain.

While audiences may not necessarily be able to read the written word or understand a spoken language, the arts have been a means to capture and indelibly mark historical moments. We are at a moment of convergence. As monuments to the early Chinese pioneers are being marked, particularly in California and Nevada, the glaring question was how to Romanize Gold Mountain. Is there really a standard? Do we honor the dialect or sub-dialect and the nuances and variations of neighboring Southern China locales? The best solution might be to have the Chinese characters and allow those closest to the monument decide on the English phonetic representation associated with the dialect or sub-dialect of those early pioneers.

The concept of a Chinese American Museum at our nation’s capital began in 2017 and just a year later a five-story 1917 Beaux-Arts building was acquired and has been undergoing renovations to present exhibitions on historical and contemporary artifacts and interpretations, Chinese American art, cultural and educational events, and interactive multimedia experiences. Coinciding with this month’s opening of the Chinese American Museum – another premiere, Nancy Yunhwa Rao, professor of music, Mason Gross School of the Arts, Rutgers University will be speaking on 170 years of Chinese Opera in America. I will be tuning in virtually. No doubt much of the presentation will speak to Cantonese opera and bring back memories for me as a very young child accompanying Gung gung and Po po to live performances in San Francisco Chinatown and listening to Gung gung’s 8-track tapes of Cantonese opera in their opulent Nob Hill home. My mother and father’s romance started on my father’s first trip to San Francisco as an officer with the Chinese Naval Academy, relocated from China to Taiwan. Their shared Seun Dak roots and love of Cantonese opera bridged the Pacific Ocean and four long years of correspondence before Dad immigrated to San Francisco.

What will tonight’s premiere performance mean to you personally? What will it mean globally? Perhaps there are stories yet to be uncovered in your immediate family, particularly among the first-generation immigrants. And, we need only look at the headlines on global immigration. Humanitarianism mixed with rejection and suffering. But, always the resilience of the human spirit.

JULIE D. SOO is a senior staff counsel with the California Department of Insurance and is charged with prosecuting enforcement cases among her regulatory duties. She has served on numerous nonprofit and community boards and volunteers in a variety of community causes, including civil rights education, campaign work, and community health advocacy.

A fourth-generation San Franciscan, she is a Lowell High School alumna and holds an A.B. with a double major in Pure Mathematics and Statistics from U.C. Berkeley, an M.A. in Applied Mathematics from U.C. San Diego, and a J.D. from Golden Gate University School of Law.

Julie is well-known for her past work as a journalist with AsianWeek, a pan-Asian national weekly based in San Francisco, where she covered breaking stories, provided legal and political commentary, and wrote about Asian American history and notable figures. She appeared on New California Media, a public television news roundtable for California’s ethnic news community, and served as a guest host for Voice of the Neighborhood, a political radio talk show targeted to the Bay Area Cantonese-speaking community. She was selected as a 2006 California Endowment Health Journalism fellow based on her story about a Chinatown shooting where six youths were wounded and her discovery that San Francisco’s leading trauma center lacked interpreters past late evening hours to help non-English proficient patients and families. The story caught the attention of the Mayor, Chief of Police, and hospital administrators and led to policy changes. Julie has also served as a legislative aide and advisor to members of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors.

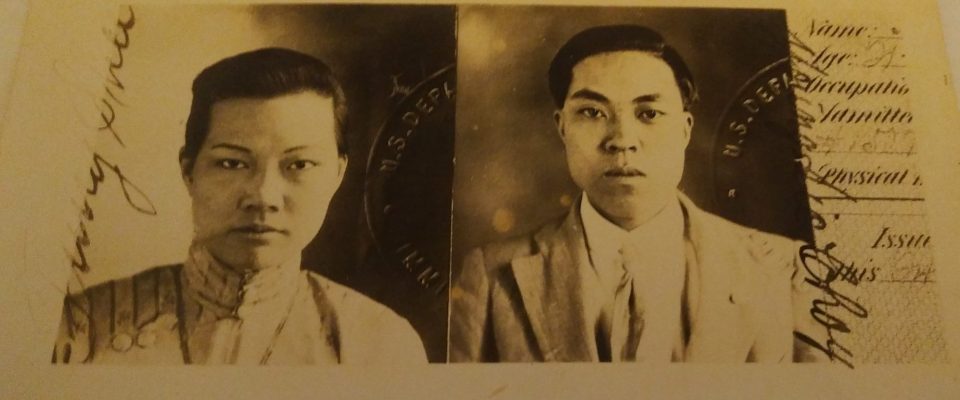

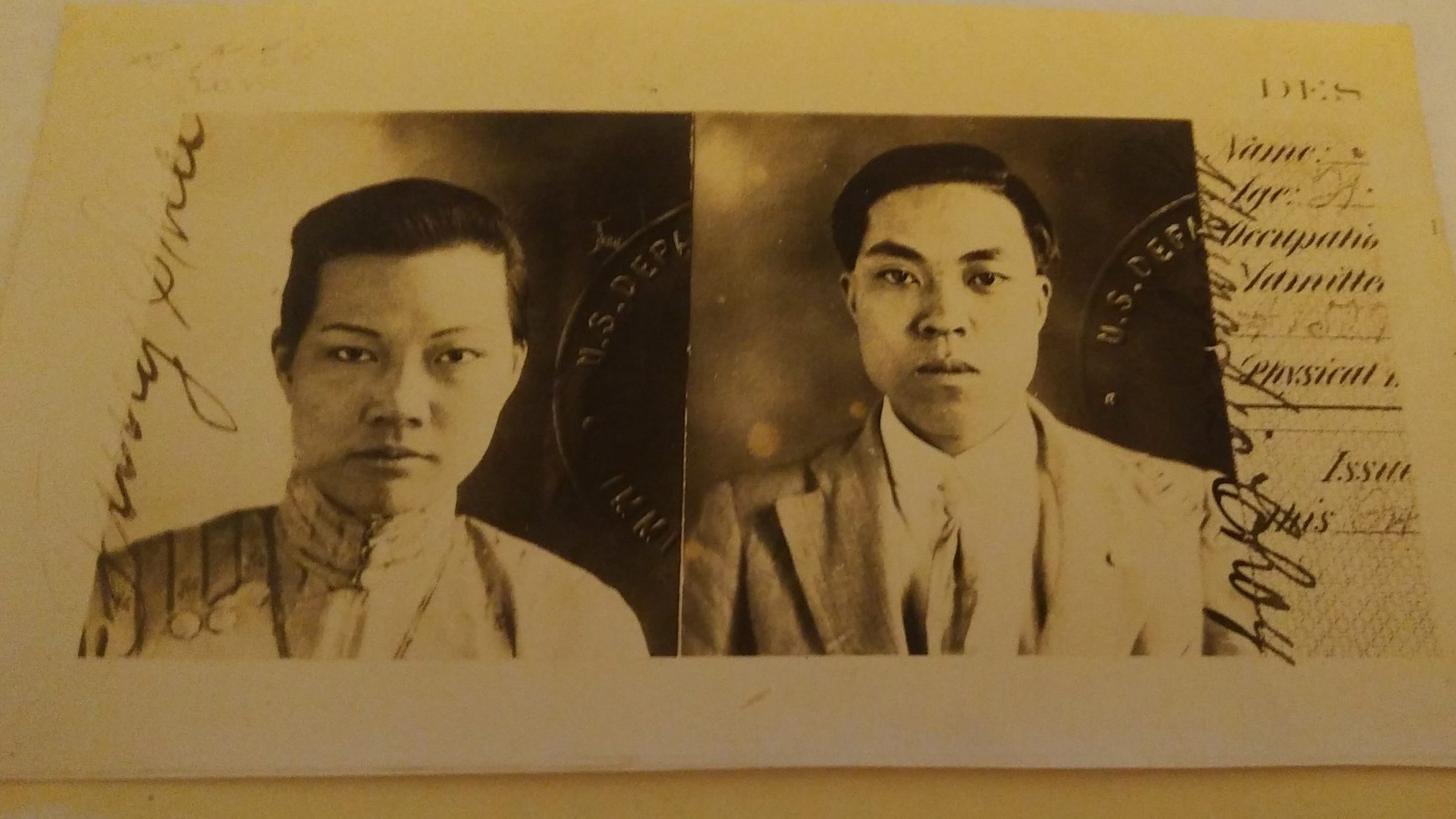

Gung Gung and Po Po, circa 1915. Photo courtesy of Julie D. Soo.

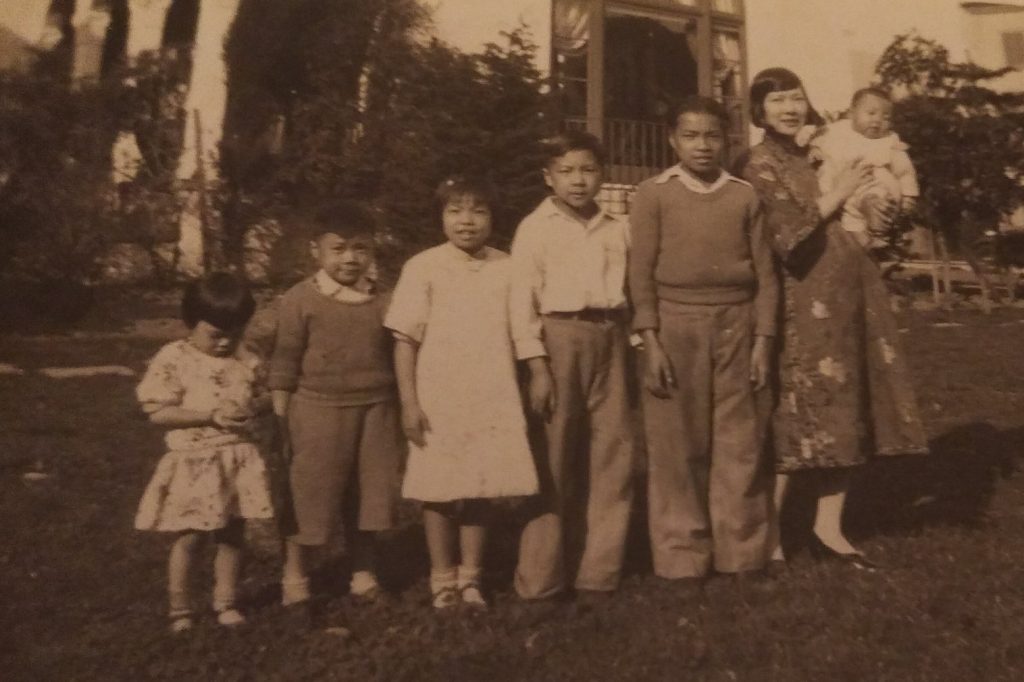

Left: Po Po and Gung Gung, circa 1940s. Center: With Family, 1940s. Right: Po Po and Gung Gung, 1960s.

Photos courtesy of Julie D. Soo.

Julie’s fondest childhood memories were of visits from foggy Twin Peaks to Nob Hill and spending overnight weekends with her maternal grandparents, Gung gung and Po po – George Sichoy Young and Quai Hing Fung Young – a couple best known for the first and only fur shop in San Francisco Chinatown – the Modern Fur Shop – that operated from the 1920s to the 1960s. They would walk to Chinatown to take in Chinese films or Cantonese opera.

Grandparents George Si Choy Young and Quai Hing Fung Young. Ferry Building, San Francisco, 1925.

Photo courtesy of Julie D. Soo.

Gung gung’s parents immigrated to San Francisco in the late 1880s from the Seun Dak District of Guangdong Province. They returned to China before the 1906 earthquake but Gung gung later joined them some five years later to finish his education and to marry Po po. Gung gung returned to San Francisco on his own in 1915 before sending for his bride. Po po, though married to a U.S. citizen, endured six months on Angel Island.

Po Po and children, circa 1931. Photo courtesy of Julie D. Soo.

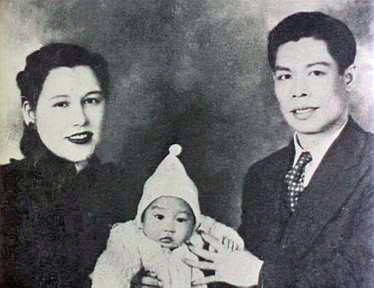

Lee Hoi-chuen, a Cantonese opera star from Hong Kong with Seun Dak District roots, toured in San Francisco and the United States and became friends with Gung gung and Po po. It was during the tour in 1940 that Lee’s son Bruce – Little Dragon — was born at Chinese Hospital.

Photo: Grace Ho and Lee Hoi-chuen with baby Bruce Lee.

By Unknown author – 搜房网电影人生, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=27804428

These same ancestral roots brought Julie’s father to a regional family association in Chinatown during a 1955 visit to the U.S. for training as a young naval officer with a maritime mechanical engineering degree from the Chinese Naval Academy. Gung gung invited Stephen Hsi-fen Soo home for dinner where he caught the eye of Julie’s mother Mabel. Their common ancestral roots and love of Cantonese opera made for a love match. After four years of correspondence, Stephen decided to leave his military career with the Republic of China and join Mabel in San Francisco. In his retirement, Julie’s father performed as an amateur in Cantonese opera under the tutelage of retired Cantonese opera stars through the Red Bean Club.

Julie is a past board member of the Chinese Historical Society of America. In 2013, she collaborated on a documentary film on the 14th Amendment and birthright citizenship, 14: Dred Scott, Wong Kim Ark & Vanessa Lopez, and has gone on to speak at film screenings about United States v. Wong Kim Ark, the 1898 case wherein the United States Supreme Court articulated the term “birthright citizenship” in its interpretation of the 14th Amendment, the Chinese Exclusion Act, and the historic exploitation of immigrants. Wong Kim Ark was born on Sacramento Street in San Francisco Chinatown in 1873 and until the 1898 Supreme Court decision, he and others like him, though born on U.S. soil, were not recognized as U.S. citizens. This story has had great meaning for Julie because her Gung gung was born six years before the landmark case.

During the COVID pandemic, Julie was asked to edit a chapter on Wong Kim Ark for American University law professor Amanda Frost’s book, You Are Not American: Citizenship Stripping From Dred Scott to the Dreamers. Julie was also proud to be an advisor on Debbie Lum’s film – Try Harder! – on Lowell High School that made its Sundance Premiere in January 2021 and included a virtual screening with Lowell alumnus U.S. Supreme Court Associate Justice Stephen G. Breyer. The film makes its theatrical premiere in San Francisco, Los Angeles, and New York at the end of 2021.

Julie has conversational abilities in Cantonese and has studied Mandarin to further her community work.